The COVID-19 pandemic has spared none in its ravenous path across the world. Governments are struggling to fight the virus and come up with answers to deal with its social and economic fallout. Informal waste economies in the global south have been some among the most affected in this crisis.

It’s estimated that urban cities generate around 1.3 billion tonnes of waste every year, with all signs pointing to this figure multiplying in the future. While developed nations have managed to set-up their waste management systems, their developing counterparts have struggled to implement something similar and have grown reliant on informal economies that have stepped in. The kabadiwallas in India, the cartoneros in Mexico and the catadores in Brazil are just a few examples of players in these informal waste economies. They pick-up, sort, aggregate and upcycle waste - passing it along a supply chain that leads to it finally getting recycled. It’s a system that provides an essential service to society, and which some suggest works better than many formal mechanisms.

The global pandemic has had a particularly debilitating effect on these systems and their players. With lockdowns being imposed globally, waste-pickers have lost their livelihoods overnight. These daily-wage workers are already subject to social stigma, unhealthy living conditions and a lack of social security; but now they are facing an even more uncertain future as their families go hungry with no real prospect of the situation changing.

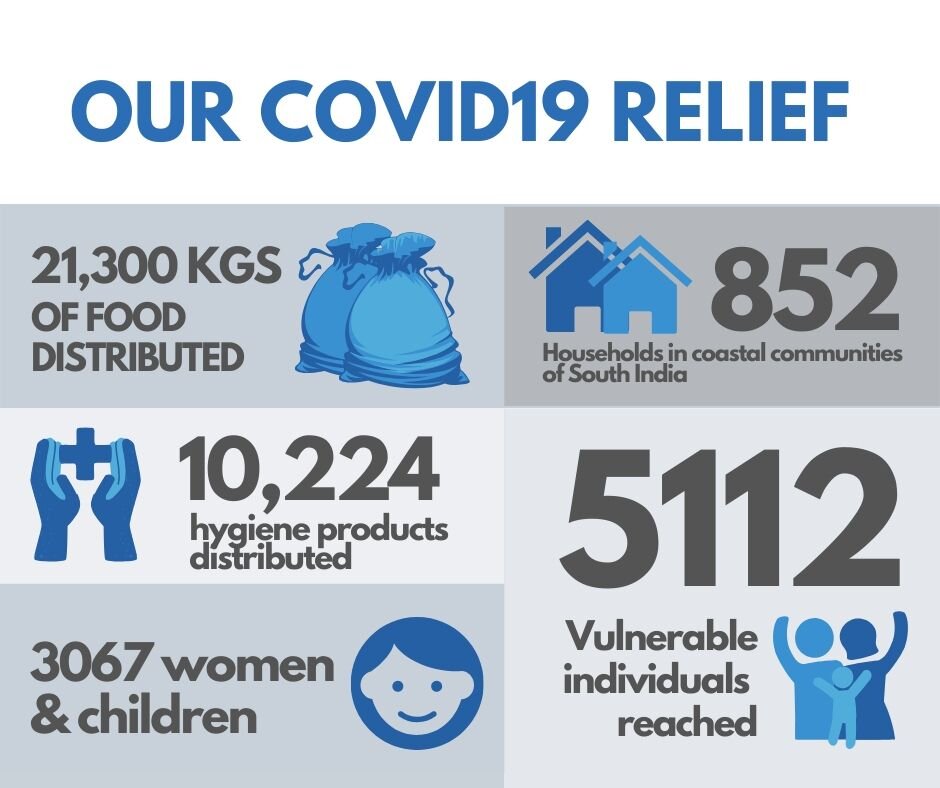

While several governments have announced monetary relief packages, most in these communities do not possess the documentation needed to access this and so are left without any governmental support. Our own surveys in the communities we work with, revealed that around 30% of the individuals do not have the necessary IDs. There have been a number of NGOs that have been working hard to provide these communities with food and supplies, including our own that has been able to provide 852 wastepicker families with essential supplies kits. However, the reality is that this is not a sustainable solution. With the world facing an economic downturn and oil prices in free-fall, the likelihood of brands forgoing sustainably sourced materials for cheaper alternatives is quite likely - placing another layer of uncertainty for these informal systems that work in recycling material.

The future of these communities is dependent on a number of factors. While the relief efforts of NGOs have been essential in the short-term, it is abundantly clear that restoring and stabilising the livelihoods of these communities is key to any long-term solution. At Plastics For Change, we’ve developed a marketplace platform that connects waste-pickers to global markets and ensures a consistent supply of high quality recycled plastic for brands - thereby creating better livelihoods for the urban poor while keeping plastic out of the ocean.

Navigating a post-COVID world will require such bold innovations within these systems and will need larger institutions to back-up the security of livelihood for these communities. For this to work, now more than ever it’s vital that consumer brands stay committed to their recycling related sustainability goals and expand on their sourcing of recycled material.

While the earth heals itself we’ve been reminded that it is our responsibility to treat the planet better. With the current increase in the use of plastic it's become even more evident of the need for us to transition to a plastics circular economy. People are looking for ways to make a difference and contribute to the betterment of the world. Brands can rise to the occasion and lead the way in affecting this change and by doing so create a culture of sustainable living. One look at the informal waste economies reveals that the need goes beyond helping the planet, it’s helping its people too. If this period of adversity has taught us anything it is that when the world comes together there is hope even in the darkest times.